One More Thing: Stories and Other Stories

by B.J. Novak

You know B.J. Novak as that guy from The Office who always looks a little fatigued, but who also looks like he could be Hugh Grant's younger brother. But if you read this book of short and very short stories, you will think of him as That Guy Who Can Really Write and Who Also Happens to Be On A TV Show. Because these stories! They amaze.

Novak's stories start somewhere familiar and end up knocking you off your chair with their originality. They deliver unexpected humor and on-point parody; they are clever and poignant and smart. Here's a great interview with Novak about the book and other stuff, in case you're interested.

Gone Girl

by Gillian Flynn

This suspenseful novel has more twists than a bag of fusilli. If you're like me, you'll need to take a swig of Mylanta every few chapters; or maybe take a break from reading to have a pot of Darjeeling and remind yourself that--thank God--mostly you can avoid dealing with sociopaths except in fiction and the occasional outlying relative. (Unless you can't, of course, in which case: sympathies.)

Gone Girl combines Stephen King-esque suspense with an insidious unreliable narrator a la Zoe Heller's Notes on a Scandal. I couldn't put it down.

The Remains of the Day

I'm happy that Mr. Ishiguro has a new novel coming out in March, his first in ten years.

by Lee Martin

Sam Brady leads a quiet, private life with his dog, Stump, until he decides to build a doghouse that looks like a ship. The doghouse attracts attention, which like the first domino, sets off a chain reaction. Sam's past begins to catch up to him. Martin presents Sam and his neighbor Arthur, his brother Cal, and other characters with vivid complexity. His storytelling reminds us that the small things matter.

Lee Martin's quiet, observant, lyrical and surprising storytelling in this little novel has made him one of my new favorite authors. I will definitely be seeking out Martin's other titles in 2015.

Lee Martin's quiet, observant, lyrical and surprising storytelling in this little novel has made him one of my new favorite authors. I will definitely be seeking out Martin's other titles in 2015.

The Remains of the Day

by Kazuo Ishiguro

This book has no right to be as fascinating, funny, beautiful, and compelling as it was. Nothing much happens--and yet by the time you get to the end, you feel like you've had a Literary Experience and you will never be the same.

I'm happy that Mr. Ishiguro has a new novel coming out in March, his first in ten years.

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

by Jonathan Safran Foer

Foer's groundbreaking literary style would normally not be my cup of tea. It's borderline stream-of-consciousness, and my undiagnosed ADD gives me enough trouble tracking the characters and settings in a traditional novel, let alone one that has multiple POVs. And yet this story sucked me in and pulled me along. Foer captures the voice of his young male protagonist perfectly; it's poignant and funny.

by Viktor Frankl

"Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms--to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way."

In telling the story of his time in the concentration camps during WWII, Viktor Frankl asserts that we have the power to find meaning, hope, and purpose in the middle of our inevitable suffering. This book is an enduring and accessible classic.

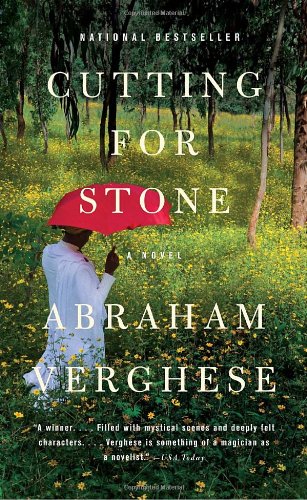

Cutting for Stone

By Abraham Verghese

It says a lot about this book that John Irving (another of my favorite authors) reviewed Cutting on Amazon: "This is a first-person narration where the first-person voice appears to disappear, but never entirely; only in the beginning are we aware that the voice addressing us is speaking from the womb!"

I'll be reading this one again.

The Hot Kid

By Elmore Leonard

I picked this up because I binge-watched all the seasons of Justified (based on an Elmore Leonard novella, Fire in the Hole) this year, and wow. Elmore Leonard's tight, packed sentences sucked me in from the first page, and I don't even know how he manages to write such vivid characters with so few words. I will definitely read more Elmore Leonard in 2015.

The Seven Storey Mountain

by Thomas Merton

Started this one a couple of years ago; put it down for a long time; and finally picked it up and read it all the way through this year. There is nothing like a good conversion story to inspire your new year.

As the child of fundamentalist, Dispensationalist parents, I learned early on to mistrust any form of Christianity that was not exactly like my own. Catholics, to me, were not "real" Christians; in fact, most Christians were quotation-mark "Christians." I'm not proud of this. But as Kathleen Norris wrote in Amazing Grace (see below), “In order to have an adult faith, most of us have to outgrow and unlearn much of what we were taught about religion.”

And Merton delivers a great pay-off, with great writing on philosophy and theology. He inspires me to love God more, and to examine my faith and practice more rigorously.

by Kathleen Norris

This was a re-read from several years ago. I picked it up again as part of my preparation for a class I taught at church. It's definitely worth re-reading. In her writing, Kathleen Norris often calls upon the writings of the early church mothers and fathers to illuminate contemporary life and faith. No one else does this like she does; she's like the modern day Thomas Merton.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

by J.K. Rowling

I read the first four Harry Potters when I was on bedrest in the hospital, pregnant with M. Peevie. M. Peevie, you might recall, just turned fourteen, and when I told her I had not read the last three books, she was shocked and horrified.

"Mom! You have to read them!" she ordered.

I told her I didn't really remember the first four, but she suggested I just re-read them. "It won't take you very long!" she predicted. She was right. They were great the second time around; and now I've started the fifth book, H. P. and the Order of the Phoenix.

To Be Near Unto God

by Abraham Kuyper

"...[w]hen clouds gather over your head, when adversity, loss and grief inflict wound upon wound in your heart, when the fig tree does not blossom, and the vine will yield not fruit, then with Habakkuk rejoice in God, because his blessed nearness is enjoyed more in sorrow than in gladness...". I am working on this.

A Public Faith: How Followers of Christ Should Serve the Common Good, by Miroslav Volf: File this one under "Mostly Over My Head"--but still well worth the time and effort to consume it.

Volf responded to Bonhoeffer's assertion that the church facing the Nazi regime was experiencing a passage through a foreign land, suggesting that outside of this context, "serious problems arise" from this perspective:

The fundamental theological problem with such an external view of Christian presence in the world is a mistaken understanding of the earthly habitats of Christian communities. It presupposes that the culture in which they live is a foreign country, pure and simple, a land bereft of God, rather than a world that God created and pronounced good.

...[I]t would contradict major Christian convictions to think that the world outside Christian communities is bereft of God's active presence. The God who gives "new birth" is ... also the creator and sustainer of the world with all its cultural diversity...Cultures are not foreign countries for the followers of Christ, but rather their own homelands...Christian communities should not seek to leave their home cultures and establish settlements outside or live as islands within them. Instead, they should remain in them and change them--subvert the power of the foreign force and seek to bring the culture into closer alignment with God and God's purposes.

This is all well and good, but I'm not sure what that looks like operationalized. And that is a whole other blog post.

Pastrix: The Cranky, Beautiful Faith of a Sinner and Saint, by Nadia Bolz-Weber: See Merton, above.

This is our God. Not a distant judge, nor a sadist, but a God who weeps. A God who suffers, not only for us, but with us. Nowhere is the presence of God amidst suffering more salient than on the cross. Therefore, what can I do but confess that this is not a God who causes suffering. This is a God who bears suffering. I need to believe that God does not initiate suffering. God transforms it.

Driftless, by David Rhodes: Many beautiful sentences in this one.

Jacob lay on his back. The stars looked back at him from ten million years ago, their light just now arriving. He wondered if there were other places in the universe where the rules of the living did not require feeding on each other--where wonder could be discovered without horror and learning the truth did not entail losing one's faith.

The Complete Stories, by Flannery O'Connor: You could teach a class based solely on the metaphors and similes O'Connor uses to talk about the sun and sky:

The sun was a huge red ball like an elevated Host, drenched in blood and when it sank out of sight it left a line in the sky like a red clay road hanging over the trees.

The sun was like a furious white blister in the sky.

The cows were grazing on two pale green pastures across the road and behind them, fencing them in was a black wall of trees with a sharp sawtooth edge that held off the indifferent sky.

The sky was bone-white and the slick highway stretched before them like a piece of the earth's exposed nerve.

OK, this post is already too long, so here are some honorary mentions from my 2014 reading list, with tiny reviews and/or quotations.

Faith Unraveled: How a Girl Who Knew All the Answers Learned to Ask Questions

by Rachel Held Evans: Exactly.

Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad: "I don't like work--no man does--but I like what is in the work,--the chance to find yourself."

Jewel, by Brett Lott: Sprawling. Well-drawn characters.

A Clash of Kings: A Song of Ice and Fire, by George R. R. Martin: Loving this series.

Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov: Beautiful writing; disturbing story.

Divergent, by Veronica Roth: The four categories were such a smart story hook, but honestly, it reads a little like a YA harlequin romance, especially once the kissing starts. This SNL spoof The Group Hopper was hilarious.

I Always Knew I Would Make It (And Other Entrepreneurial Fallacies), by Kate Koziol. This author is smart, funny, brave, and resourceful. And good at puzzling.

The Writing Life, by Annie Dillard: Finally making my way through the best books on writing. This is a classic.

Whose Body, by Dorothy Sayers: Can't believe it took me this long to read Sayers.

When You are Engulfed in Flames, by David Sedaris: Funny. Duh.

Bleak House, by Charles Dickens: Bleak, long. Very Dickensian, if you know what I mean.

That's it. What are you recommending from your 2014 reads?