I'm going to tell you why you should stop saying the word "should." And yes, I hear the irony.

Sometimes--especially around this time of year--we say that word to ourselves: I should lose weight. I should exercise more. I should read more books. I should drink less wine. I should be less crabby with my kids. I should call my mom more often. I should stop being a bad Christian.

Sometimes--especially around this time of year--we say that word to ourselves: I should lose weight. I should exercise more. I should read more books. I should drink less wine. I should be less crabby with my kids. I should call my mom more often. I should stop being a bad Christian.

We should all stop saying should to ourselves. I am trying to stop "shoulding" all over myself--but more about this in my upcoming memoir. (Props to my therapist, Doc, for that nearly homophonic pun.) But this post specifically addresses the use of the word should when it's directed at another person.

Stop saying "You should..." to other people. It comes under the heading "Unsolicited Advice: Never Give it."

Don't tell your sister who has stage three ovarian cancer that she should feel grateful that she doesn't have stage four ovarian cancer. This is an important sub-category of Stop Saying Should: Don't tell any cancer patient--or any person with any illness at all--that they should feel grateful. In fact, just stop telling people how to feel.

Don't tell your overweight friend that she should try yoga or pilates or aqua cycling or pole dancing classes.

Don't tell parents who are dealing with a child that JUST WON'T SLEEP, "Oh, you should try Dr. Sleep Nazi. I did, and now my kids sleep perfectly!"

Don't tell your son or daughter or friend or neighbor that they should spank their temper-tantrumming child, or that they should not give their children candy, or let them watch TV or play video games. Don't ever use the word "should" to your parenting son or daughter with regard to their parenting choices.

I know that your intentions are good. I know that you are only trying to be helpful. I understand that in your mind, when you offer an unsolicited "you should...", you are offering the benefit of your wisdom and years of experience.

But here's how it comes across: You know better than me. You would feel differently if you were in my shoes. You are better than me, and you would make different choices. It's easy if only I'd do it your way. You are trying to fix me.

Do you hear the condescension? That's how it feels. It's not helpful or constructive--in fact, it's counterproductive.

Stop saying "You should..." to other people. It comes under the heading "Unsolicited Advice: Never Give it."

Don't tell your sister who has stage three ovarian cancer that she should feel grateful that she doesn't have stage four ovarian cancer. This is an important sub-category of Stop Saying Should: Don't tell any cancer patient--or any person with any illness at all--that they should feel grateful. In fact, just stop telling people how to feel.

Don't tell your overweight friend that she should try yoga or pilates or aqua cycling or pole dancing classes.

|

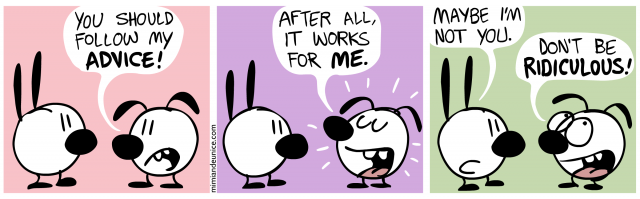

| Thanks to Mimi and Eunice for the cartoon. |

Don't tell your son or daughter or friend or neighbor that they should spank their temper-tantrumming child, or that they should not give their children candy, or let them watch TV or play video games. Don't ever use the word "should" to your parenting son or daughter with regard to their parenting choices.

I know that your intentions are good. I know that you are only trying to be helpful. I understand that in your mind, when you offer an unsolicited "you should...", you are offering the benefit of your wisdom and years of experience.

But here's how it comes across: You know better than me. You would feel differently if you were in my shoes. You are better than me, and you would make different choices. It's easy if only I'd do it your way. You are trying to fix me.

Do you hear the condescension? That's how it feels. It's not helpful or constructive--in fact, it's counterproductive.

All of this is, of course, moot if your friend/son/daughter is actually asking you for advice. Then it's OK to make suggestions--although This Blog still recommends that you do it without using the phrase "you should." Try these alternatives: "Have you tried..."; "What worked for me was..."; or "I wonder if you could..." These phrases have a degree of humility and compassion.

By the way, I should people all the time. It's an instinctive reaction, I think--when we see someone we care about struggling, we want to help, to fix, to advise. One time I told my friend Roseanne, who was struggling with money issues, "You should cancel your cable subscription." To this day, I hear myself saying that, and I cringe. Who the hell am I to tell her how to live her life and balance her checkbook? None of us know enough about another person to tell her what she should or should not spend her money on--UNLESS SHE ASKS US FOR ADVICE.

What unsolicited shoulds have you received lately? And have you dished any out?

By the way, I should people all the time. It's an instinctive reaction, I think--when we see someone we care about struggling, we want to help, to fix, to advise. One time I told my friend Roseanne, who was struggling with money issues, "You should cancel your cable subscription." To this day, I hear myself saying that, and I cringe. Who the hell am I to tell her how to live her life and balance her checkbook? None of us know enough about another person to tell her what she should or should not spend her money on--UNLESS SHE ASKS US FOR ADVICE.

What unsolicited shoulds have you received lately? And have you dished any out?